The victory of William the Conqueror’s forces over Anglo-Saxon king Harold II is well known.* One would think that a conqueror, who gave Anglo-Saxon lands to his victorious vassals and warriors might have endorsed enslaving the conquered peoples. It wouldn’t have been odd, slavery was practiced by the Anglo-Saxon’s themselves as well as a large part of western Europe.

The victory of William the Conqueror’s forces over Anglo-Saxon king Harold II is well known.* One would think that a conqueror, who gave Anglo-Saxon lands to his victorious vassals and warriors might have endorsed enslaving the conquered peoples. It wouldn’t have been odd, slavery was practiced by the Anglo-Saxon’s themselves as well as a large part of western Europe.

However, William of Normandy’s conquering of England may well have started the downfall of slavery in that country. A fascinating article by noted historian Marc Morris** published in the March 2013 issue of History Today, follows both the demise of slavery in England and the scholarly perception of the practice. Morris explains much that might baffle those who may have believed that slavery never existed in England or that it was practiced until abolished by Britain’s Slavery Abolition Act of 1833.

While the legal date may be 1833, the downfall of slavery in Britain began with the Battle of Hastings. Morris explains:

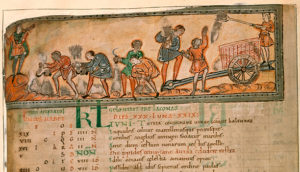

The political fragmentation of France during the 10th century, the increase in knights and growth of castle-building, had made violence and warfare more endemic and, precisely for this reason, better regulated. Warriors concluded it was better to capture and ransom each other in war rather than risk death every time they took to the battlefield. At the same time the Peace of God movement urged the protection of non-combatants. By the 11th century young men and women were no longer a legitimate target in warfare, to be led away in chains once the fighting was over.

What happened in 1066, therefore, was that a people who were still comfortable with slavery and conducted war as a slave-hunt were conquered by a people who had recently abandoned both practices. This left the Normans with something of a moral dilemma: whether to respect the culture and customs of those they had conquered, or to impose their own set of values. Clearly the Conquest was not followed by any great edict of emancipation; if 20 or 30 per cent of the population were classed as slaves, such a move would have been wholly impractical. Nevertheless, where it can be measured we do witness a marked decline. Domesday Book shows that between 1066 and 1086 the number of slaves in Essex fell by 25 per cent. Some of this, of course, may have been due to the confusion caused by the Conquest itself, rather than by the moral scruples of England’s new Norman masters, many of whom (as Domesday also shows) were quite content to keep slaves on their newly acquired manors.

Prior to electronic communications, cultures changed very slowly. The demise of slavery in Britain took place over a period of approximately eight hundred years. Not to be lauded in any way, slavery was a world-wide practice, until cultures, mores, and laws changed. But in the case of Britain we can point to October 1066 as a high-water mark not in the cause of bondage but in the cause of independence.

Prior to electronic communications, cultures changed very slowly. The demise of slavery in Britain took place over a period of approximately eight hundred years. Not to be lauded in any way, slavery was a world-wide practice, until cultures, mores, and laws changed. But in the case of Britain we can point to October 1066 as a high-water mark not in the cause of bondage but in the cause of independence.

I’d love to know what you think about this discussion initiated by my research into medieval October events. Please leave a comment. Thank you.

*http://www.thefinertimes.com/Middle-Ages/events-in-the-middle-ages.html

**Published in History Today Volume 63 Issue 3 March 2013. Marc Morris is a historian and broadcaster. His most recent book is The Norman Conquest (Hutchinson, 2012). https://www.historytoday.com/marc-morris/normans-and-slavery-breaking-bonds

Recent Comments